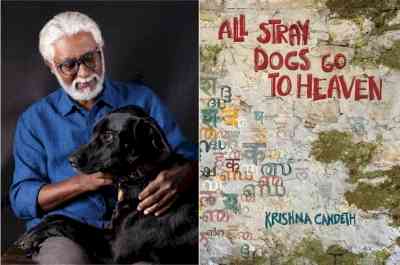

Krishna Candeth's debut novel a dialogue with 'buried facts & feelings' (IANS Interview)

A book that explores the power of love, friendship, family, and the elusive idea of home, and compels us to revisit our own ideas of truth, the self and reality "All Stray Dogs Go to Heaven" by Krishna Candeth is an astounding debut novel.

VISHNU MAKHIJANI

New Delhi, March 26 (IANS) A book that explores the power of love, friendship, family, and the elusive idea of home, and compels us to revisit our own ideas of truth, the self and reality "All Stray Dogs Go to Heaven" by Krishna Candeth is an astounding debut novel.

Told from multiple perspectives and weaving past and present, dreams and reality the book revolves around relatable themes and emotions. A collection of stories that happened a long time ago and will most certainly happen again,

The book comes across as a string of stories that come together as one big story. How did he go about writing the book in the way that he has?

"You should never ask author show they go about writing their books because the simple answer is They don't know," Candeth told IANS in an interview, adding: "Everything they write supposedly comes from their imagination but as writers they don't know how that imagination works."

"It's almost as though they were writing with a dripping brush, and leaving little dabs and stains as they went along! The real question has to do with how stories are told. Are 'good stories' good because of a certain succession of events or are they good because of the way those events are narrated," said Candeth, who's the nephew of Lt Gen KP Candeth (retd), who played a key role in the liberation of Goa and later served as Deputy Chief of Army Staff.

Candeth noted that South India has a very muscular tradition of telling stories or kathas and Indian storytelling, in general, is complex and hugely entertaining; in fact, a distinctive feature of the "Kathasaritsagara", the great compilation of stories from the eleventh century by Somadeva, is the telling of the same story twice, once in its abbreviated form and once at length!

He point out that for a text written in the eleventh century, "that is amazingly inventive, and modern, if you want to call it that."

There are no chapters in the book, only subheadings; how's that?

Candeth said: "I was vaguely conscious of the fact that this was a structure used mostly in works of non-fiction but I went ahead with it anyway because that was how I had originally conceived the book.

"There may be more radical reasons for this particular decision but I am not fully aware of them. You might call the structure episodic. It allowed me the luxury of writing certain episodes ahead of others, and that was an advantage because I knew how they were going to link up in the end.

"Also, the episodic structure allowed the story to expand, to grow sideways rather than go shooting off towards some intended conclusion. I can't remember who it was who said that you don't write a book as the crow flies."

On a more mundane level, the episodic structure allows the reader to skim through the pages of the novel with a firm thumb and forefinger, stop and explore what a subheading has to offer, and then move backwards or forward as the mood dictates!

"A novel in its traditional form, offers a very particular linear pleasure but there is a more ambiguous delight in absorbing the information or random observations from episodes in no particular order," Candeth said.

As for the novel being a story about stories, he agreed, saying: "It's about all those thoughts and feelings that are forever knocking about in the great bazaar of our heads and hearts, and the stories big and small, half or fully formed that often appear without warning."

How does he hope to strike a chord with readers?

Candeth explained: "When writing 'Stray Dogs', I would think of it as some sort of an imagined report about something a friend and I had talked about a long time ago and then forgot, about buried facts and buried feelings, about things -- cruel and unforgiving -- that had happened in the past and might well happen again in the future.

"I don't really have a particular reader in mind. Readers have so many choices these days-they can walk into a bookshop and pick up books that cater to their every mood. There are all kinds of readers, and quite often the same incident or observation in a novel may draw quite unexpected responses from different readers.

"If there was something I would like the reader to be left with, it is the sense of how all the stories and events add up and accumulate in the course of the narrative, and leave us at the end with the madness and the marvels we are capable of as human beings, and how, in spite of everything, there is a mutual vulnerability that unites all of us.

"I suppose at one level we all write the books we like to read; there is a layer of sediment we kick loose and bring up to the surface when we write a novel, and sometimes the colour or density of that sediment may both attract and repel readers. Some may respond to the spiritual, others to the political, sexual or joyful aspects of it.

"The thing to remember is that you can't separate the various elements in a novel, put them in boxes and say, This is political, this is spiritual, sad, joyful etc. At the heart of a good novel there is a kind of emotional truth and that truth contains ALL those elements.

"I like to think of the novel (or any writing, for that matter) as a small device that, when it works well, ignites in us a sense of wonder. We try to discover or uncover something when we write. We may not be sure what it is but it often turns out to be some form of that same emotional truth. One hopes, of course, that the reader will come to detect it and, in the course of his or her reading, be affected by it."

The book weaves past and present, dreams and reality together, and in the process also brings in multiple perspectives through different characters. How did he go about sketching the characters in the book?

Talking about the influence of Milan Kundera on his work, he said: "In 'The Unbearable Lightness of Being', a book that made a huge impression on me when I first read it many years ago, Milan Kundera talks of how characters are not born like people of a woman; they are born of a situation, a sentence, a metaphor containing in a nutshell a basic human possibility that the author thinks no one else has discovered."

He added: "By the way, I believe the Nobel Committee would do itself a big favour if, for one brief moment, they put all political considerations aside, and awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature to Milan Kundera who is 93 years old and, quite simply, one of the great or probably the greatest living novelist of our time."

Candeth continued: "Coming back to the characters in the novel, I had imagined most of them as vagabonds, as stray dogs who wander the streets of their own imaginations. Like a lot of us, they live simultaneously in the past and in the present, in day dreams and delusions, and you can call the resulting mixture 'reality' if you so desire.

"The reason why all these states of mind and place co-exist on the page without being too disruptive has to do really with the form of the novel. It is so wonderfully elastic: it absorbs everything; it accommodates, expands, it has room for everything. It can be in one place at one moment, and all over the place, the next."

He concluded by adding: "To complete the thought, I hope the novel is never in danger of being too moralistic or puritanical, because it is really the most generous and unpuritanical of forms."

From the very beginning, the idea was to benefit from a narration that alternates without breaks between the past and present of the characters, and juxtaposes what is happening in their minds with what is happening outside it. He don't particularly care for a God-like narrator who eats samosas and pretends to know everything, Candeth concluded.

(Vishnu Makhijani can be reached at [email protected])

IANS

IANS