Scientists create first synthetic embryos in lab without sperm or eggs

Scientists in Israel have grown synthetic embryo models of mice outside the womb by starting solely with stem cells cultured in a petri dish - that is, without the use of fertilised eggs.

Jerusalem, Aug 4 (IANS) Scientists in Israel have grown synthetic embryo models of mice outside the womb by starting solely with stem cells cultured in a petri dish - that is, without the use of fertilised eggs.

The team from Weizmann Institute of Science grew a synthetic embryo model solely from naive mouse stem cells that had been cultured for years in a petri dish, dispensing with the need for starting with a fertilised egg.

Before placing the stem cells into an electronically controlled device, the researchers separated them into three groups. In one, which contained cells intended to develop into embryonic organs themselves, the cells were left as they were.

Cells in the other two groups were pretreated for only 48 hours to overexpress one of two types of genes: master regulators of either the placenta or the yolk sac.

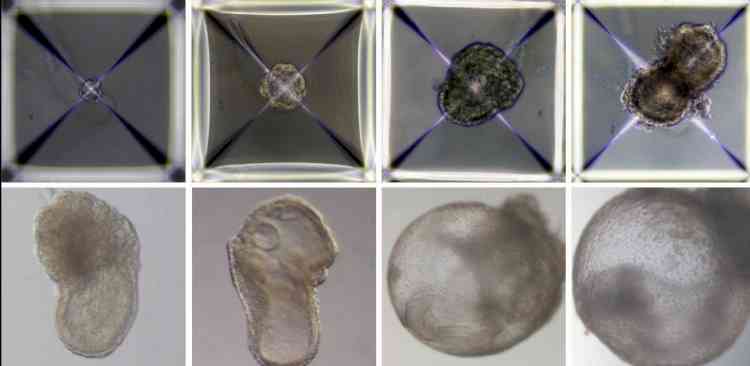

Soon after being mixed together inside the device, the three groups of cells convened into aggregates, the vast majority of which failed to develop properly. But about 0.5 per cent -- 50 of around 10,000 -- went on to form spheres, each of which later became an elongated, embryo-like structure.

The team were able to observe the placenta and yolk sacs forming outside the embryos and the model's development proceeding as in a natural embryo, they described in the journal Cell.

The synthetic models developed normally until day 8.5 -- nearly half of the mouse's 20-day gestation -- at which stage all the early organ progenitors had formed, including a beating heart, blood stem cell circulation, a brain with well-shaped folds, a neural tube and an intestinal tract.

When compared to natural mouse embryos, the synthetic models displayed a 95 per cent similarity in both the shape of internal structures and the gene expression patterns of different cell types. The organs seen in the models gave every indication of being functional.

"Our next challenge is to understand how stem cells know what to do -- how they self-assemble into organs and find their way to their assigned spots inside an embryo. And because our system, unlike a womb, is transparent, it may prove useful for modelling birth and implantation defects of human embryos," said Prof. Jacob Hanna from Weizmann Institute of Science, who headed the research team.

The method opens new horizons for studying how stem cells form various organs in the developing embryo, and may one day make it possible to grow tissues and organs for transplantation using synthetic embryo models.

"Instead of developing a different protocol for growing each cell type -- for example, those of the kidney or liver -- we may one day be able to create a synthetic embryo-like model and then isolate the cells we need. We won't need to dictate to the emerging organs how they must develop. The embryo itself does this best," Hanna said.

IANS

IANS