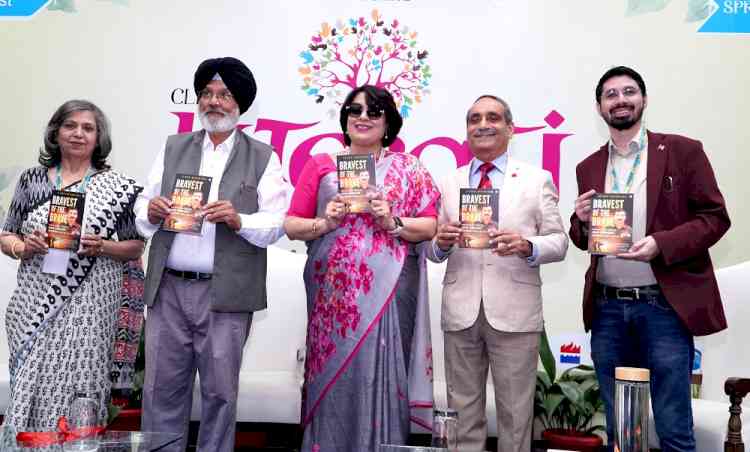

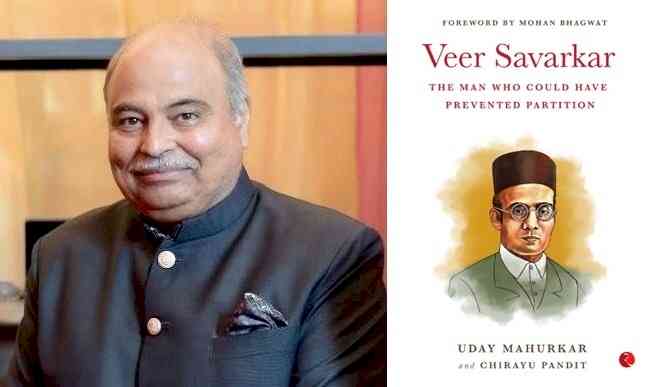

Setting the record straight on Veer Savarkar (Book Preview)

New Delhi, Oct 5 (IANS) Veer Savarkar: The man who could have prevented Partition by Uday Mahurkar and Chirayu Pandit is a candid, self-professed effort to set the record straight on the rightwing icon. Such an attempt would need to pitch Savarkar against the leading lights of the time, and it does so.

The book, expected out later this month, suggests a retelling of history and makes two essential points - the missed opportunities during the national movement that Savarkar views might have helped avoid, and the times that he seemed prescient in identifying key problems, primarily on national security.

The preface by Mahurkar says: The epilogue in this book deals with how the absence of Savarkarian vision has affected our national psyche and prevents us from realizing our true potential. It illustrates with examples how the lack of Savarkarian vision has led to distortions in history which, in turn, have affected our national vision and left our mind fractured in many other areas. It further analyses what today's India would have been like had Savarkarian vision been implemented soon after Independence.

A reading of the preface suggests a link between nationalism and militarization. At this point, Savarkar is positioned against Gandhi, Congress and non-violence. Mahurkar describes how he tries to analyse Savarkar's belief vis-a-vis the Congress that complete non-violence against an 'unprincipled enemy' is a perversion of virtue. It goes on to suggest that the Balakot strike was based on this belief. Mahurkar, in fact, draws a causal link between the basis of Pakistan and the 'Muslim-appeasement policy of the Congress'.

It is natural, therefore, that such a line of thinking should lead to the diminution of Gandhi - even Sardar Patel does not appear as the great unifier as he was a signatory to the resolution to give provinces the right to self-determination. The book recalls a story, now increasingly in the public domain, of the meeting between Britain's post-War prime minister Clement Attlee and West Bengal's then acting governor P.B. Chakraborty where the former noted that Gandhi's influence on Britain's decision to grant independence to India was 'minimal'. It refers instead to the role of the Azad Hind Fauj and the threat of Indian soldiers returning from Europe at the end of WWII as more notable reasons.

This fits in neatly with the Savarkarian postulate. Any interpretation of history, especially, one that carries a political message, would be selective in approach. The role of the Azad Hind Fauj, the naval uprising and the threat of returning Indian soldiers notwithstanding, there were other factors that were just about as important - like Britain's own diminished position in the post-War global power equations, America's role in leaning on Britain on the issue of India's independence. And of course, Gandhi's unquestioned role since he came on the scene to organise the Indian masses, his great skills as a communicator that facilitated this, and giving them a moral compass to be guided by.

The tepid presentation of Gandhi is perhaps natural for a book on Savarkar, who had been a critic of the Mahatma. Mahurkar and Pandit capture the essence of Savarkar's Hindutva when they cite his call to Hindus to join the British Indian forces in 1939. They say that two years ago, in 1937, he had suspected that separatist Muslims would demand India's partition. His call to Hindus was aimed at making sure they got arms training in view of the "future threat to the unity and integrity of India".

Mahurkar notes Savarkar had marked that Hindus were fewer in number in the army on the basis of population-ratio. And that had he not given the call for militarization of Hindus, Pakistan would have "tried to swallow more areas of partitioned India apart from Kashmir".

There is a view that Savarkar has been under represented in the national movement, that he is an unsung hero of Indian history, and that his Hindutva -- for which he has been reviled by ideological opponents -- was both pragmatic and modernist. This book could provide the space and the argument to fill that gap.

One of the attractions of the book is a foreword by RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat who says, "Savarkar did not get his due even in free India". He also says how the Hindutva icon could rightly anticipate the future, especially on issues of national security.

IANS

IANS