Soon get vaccines via skin patches, no injection needed

A novel mobile vaccine printer, developed by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US, may one day help people get vaccinated via skin patches, eliminating the need of needles.

New York, April 25 (IANS) A novel mobile vaccine printer, developed by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US, may one day help people get vaccinated via skin patches, eliminating the need of needles.

The vaccine printer, which can fit on a tabletop, can be deployed anywhere vaccines are needed. It could also be scaled up to produce hundreds of vaccine doses in a day.

"We could someday have on-demand vaccine production," said Ana Jaklenec, a research scientist at MIT's Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. "If, for example, there was an Ebola outbreak in a particular region, one could ship a few of these printers there and vaccinate the people in that location."

The printer produces patches with hundreds of microneedles containing vaccines. The patch can be attached to the skin, allowing the vaccine to dissolve without the need for a traditional injection. Once printed, the vaccine patches can be stored for months at room temperature.

In a study appearing in the journal Nature Biotechnology, the researchers showed they could use the printer to produce thermostable Covid-19 RNA vaccines that could induce a comparable immune response to that generated by injected RNA vaccines, in mice.

Most vaccines, including mRNA vaccines, have to be refrigerated while stored, making it difficult to stockpile them or send them to locations where those temperatures can't be maintained. Furthermore, they require syringes, needles, and trained health care professionals to administer them.

Instead of producing traditional injectable vaccines, the researchers decided to work with a novel type of vaccine delivery based on patches about the size of a thumbnail, which contain hundreds of microneedles.

Such vaccines are now in development for many diseases, including polio, measles, and rubella. When the patch is applied to the skin, the tips of the needles dissolve under the skin, releasing the vaccine.

The "ink" that the researchers use to print the vaccine-containing microneedles includes RNA vaccine molecules that are encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles, which help them to remain stable for long periods of time.

The ink also contains polymers that can be easily moulded into the right shape and then remain stable for weeks or months, even when stored at room temperature or higher.

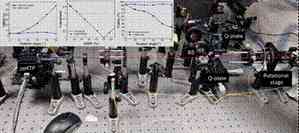

Inside the printer, a robotic arm injects ink into microneedle moulds, and a vacuum chamber below the mould sucks the ink down to the bottom, making sure that ink reaches all the way to the tips of the needles. Once the moulds are filled, they take a day or two to dry.

The current prototype can produce 100 patches in 48 hours, but the researchers anticipate that future versions could be designed to have higher capacity.

IANS

IANS